By Naipanoi Lepapa

They are brilliant, unseen, and unheard intellectual ghosts who trade knowledge for survival.

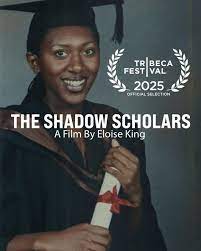

The Shadow Scholars is an unflinching and deeply humane exploration of a billion-dollar underground industry in which Kenyan graduates ghostwrite academic essays for students in the West.

It is a film that peels back the layers of “contract cheating” not simply to expose academic dishonesty, but to question global inequality, the commodification of education, and the ethics of survival.

The documentary is anchored by researcher and sociologist Patricia Kingori, a Kenyan-British and the youngest female black professor in the 925-year history of the University of Oxford.

A Hidden Industry in Plain Sight

The Eloise King’s documentary situates Kenya as the global epicenter of academic ghostwriting, estimating that around 40,000 writers, accounting for nearly 72% of the global industry, are based there.

It is not simply a fringe operation but a $7 billion-a-year economy that thrives in plain sight. A quick Google search reveals countless essay mills, yet the depth of the industry is largely unknown to those who rely on its services.

The 98 minute film follows the process with striking clarity. Students majorly in the USA, UK, Australia, China, and elsewhere upload their essay instructions, and Kenyan writers, dubbed “shadow scholars”, deliver polished and thoroughly referenced papers, often faster and of higher quality than the students themselves could produce.

The irony is palpable because while Western universities tout academic integrity as a pillar of their mission, their students outsource intellect to anonymous writers thousands of miles away.

Human Faces, Human Voices?

At its core, the film executive produced by Steve McQueen is about people, not just an industry. Many of the writers interviewed began ghostwriting while still students themselves, pushed into it by financial need and a lack of viable opportunities after graduation.

The work is intense, with essays and dissertations coming in at odd hours, with tight deadlines and high expectations.

To protect their anonymity, writers usually adopt fake online identities, using white profile photos to appeal to clients’ biases, and VPNs to log into student portals overseas. These details reveal the sheer scale of the deception and the vulnerability of those behind it.

In conversations with the ghost writers, Professor Patricia Kingori portrays them with dignity, allowing them to explain their choices in their own words.

They speak openly about why they do the work, including the urgency of paying bills, the lure of quick and reliable income, and the stark reality that ghostwriting pays far better than most legitimate jobs available to young graduates in Kenya.

For them, it is not an act of rebellion against academia but a means of survival in an economy that undervalues their talents.

Ethics in Tension

The documentary does not shy away from moral ambiguity. Professor Kingori, who guides much of the narrative, presses both writers and institutions to reflect on what is truly at stake. Some writers confess they feel no guilt.

Tricia Bertram Gallani, the Director of San Diego Academic Integrity Office, observes, “Their justification of not feeling bad is part of them being human.” For them, the transaction is work-for-hire, which is no different than other forms of intellectual labor.

Gallani, however, stresses that universities should not just focus on producing graduates because their aim should be to graduate ethical professionals. The stakes are not just academic but societal.

We should all ask, if future professionals cheat their way into qualifications, what becomes of trust in expertise? Yet, as Professor Kingori points out, the writers normally do not see the students themselves as unethical because the pressure to succeed in hyper-competitive systems is overwhelming, and outsourcing assignments becomes a survival strategy for both client and writer.

Quality, Speed, and the Irony of Outsourcing

One of the most striking elements the film reveals is the sheer professionalism of the writers. Essays are meticulously checked and referenced using the same plagiarism-detection tools, like Turnitin, that universities deploy.

Writers can craft multiple essays in a single day at any education level and deliver them within impossible deadlines. This does not speak about dishonesty alone but to a highly skilled, efficient workforce, paradoxically excluded from the very institutions that benefit from their labor.

The result is a paradox, where Western universities, many elite and prestigious, tacitly rely on the intellectual capacity of third-world countries while simultaneously decrying academic dishonesty. The film asks a cutting question: who is truly exploiting whom?

AI and the Threat of Erasure

No contemporary discussion of academic writing can ignore artificial intelligence, and King integrates this tension thoughtfully.

Writers express anxiety that AI tools like ChatGPT may make their work obsolete, even as they recognize that such tools cannot fully replicate human judgment, nuance, and contextual understanding.

Professor Kingori warns against a blind reliance on machines, reminding us that education is not simply about outputs but about cultivating ethical and critical thinkers.

Ironically, AI is also used within the documentary itself, including facial-masking technologies that disguise participants to protect their identities. This visual decision is haunting because the very tools threatening the industry also render its workers invisible, once again effacing the human beings whose intellect sustains global academia.

Where the Film Excels

The Shadow Scholars is at its strongest when it humanizes the industry. Viewers are invited not to dismiss ghostwriters as cheats but to understand them as people navigating limited options in a deeply unequal global system.

The idea of centering Kenyan voices enables the film to disrupt a narrative that typically pathologizes African economies as corrupt or informal, instead revealing ingenuity, resilience, and skill.

The documentary also succeeds in challenging simplistic binaries of right and wrong. Rather than moralizing, it explores contract cheating as a symptom of broader systemic failures, including underfunded local economies, global inequality, and the commercialization of higher education in the West.

Where It Falls Short

The film is not without gaps. While it powerfully indicts Western institutions for benefitting from this shadow economy, it stops short of fully interrogating the role of African governments and local systems.

Why do so many highly educated Kenyans find themselves forced into ghostwriting in the first place? What does this say about structural unemployment, policy failures, and educational investment at home?

Similarly, the film raises but does not fully unpack the complicity of online platforms that openly host essay mills. It focuses primarily on the human angle, which misses an opportunity to expose the corporate and systemic enablers of the industry.

A Mirror to Ourselves

Despite these limitations, The Shadow Scholars is a deeply important work. It forces audiences, especially in the West, to confront uncomfortable truths. The pressure that drives students to outsource their learning mirrors the pressure that drives Kenyan graduates to ghostwrite.

Both are products of the same system: a global academic economy obsessed with credentials, rankings, and outcomes, at the expense of genuine learning.

The film ultimately becomes less about cheating and more about justice. What does it mean when intellectual labor is bought and sold across borders in ways that perpetuate old hierarchies? What does it reveal about the true beneficiaries of higher education? And perhaps most urgently, what future awaits if education itself becomes fully commodified?

Conclusion

Eloïse King has crafted a film that lingers long after the credits roll. The Shadow Scholars is not just an exposé of contract cheating; it is a meditation on invisibility, survival, and inequality.

It compels us to reckon with the uncomfortable possibility that the systems we trust, including universities, technology, and the promise of meritocracy, are sustained by unseen hands, whose brilliance remains uncredited.

Ultimately, viewers have to answer these questions: Whose knowledge counts? Whose labor is visible? And what do we lose when the pursuit of education becomes just another market transaction?

More Stories

Safaricom Director Honored with Global Social Innovation Award

Cledun Realtors Expands Thika Housing Project with Prestige Court Phase II

Former Ichagaki MCA Dr. Mwangi Joins UDA for Murang’a Senatorial Race